Of

Men and Horses

By

Joe Greig

The central hub of the Winchester Cattle Company is on the lower stretch of the Big Wind River, above Diversion Dam, but it also includes several other ranches in the high country to the west where the cattle are pastured in the summer.The lower ranch is situated at the foot of the Bull Lake glacial moraine which creates a high bluff from which to survey the Wind River valley east for several miles. The valley is a splash of green on grey: the lush hay fields, stately cottonwoods along the river, and the sage covered bluffs on either side; these carved over millennia by water flowing from the Absaroka and Wind River Ranges of the Rocky Mountains.In his twenties, Bob migrated down the Wind River from the Crowheart country to work for Jack and Albert Winchester when I was not yet a teenager. He rode through the gate to the ranch, a blond, blue-eyed, lean cowboy type of a man; hard muscled but with a big share-it-with-me smile on his face. When Bob smiled at us we grinned back. He was astride a sorrel horse he called Rusty who, compared to some of the horses I was used to riding, looked like he had breeding. The Winchester kids and I looked forward to taking this horse for a gallop whenever the opportunity offered itself, but we soon found out that only Bob could ride this horse. Rusty bucked off everybody else, pronto!

Like most Winchester ranch hands, Bob didn't herd cattle much except during the spring and fall cattle drives to and from the mountains above the town of Dubois, a distance of some sixty-five miles to the west. The first job Albert ever gave him was to help clear an area of sage brush and rocks for an alfalfa field. The field lay at the foot of the moraine so Albert and Bob used a lot of dynamite to blow the big boulders out of the ground, then hooked onto them with a log chain, and dragged them with a tractor to the river.

Over the next few summers I worked with Bob on the ranch, and I give him considerable credit for teaching me how to work, particularly instilling in me the virtue of not complaining or dilly dallying, tendencies he disapprovingly pointed out in some of the younger hands. A job was to be engaged and finished as quickly and thoroughly as possible. He had no tolerance for slackers.

His horse, Rusty, was pastured with the other ranch horses, but when Bob wanted to ride all he had to do was whistle and Rusty would leave his field mates and come to Bob to be saddled. They seemed to have a special bond between them, although I suspected Bob nurtured it by slipping Rusty some oats from time to time.

Bob hauled many a load of hay to the cows on this rack.

At Mom's funeral I asked Bob about Rusty. He was amazed that I remembered the horse by name, and began telling me the most interesting and surprising bits of the horse's history.

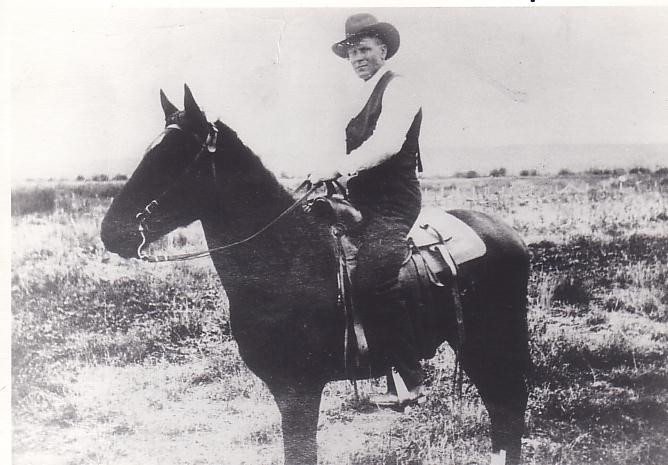

Later he wrote telling me more about himself and Rusty, and sent photographs to personalize his narrative. He began with a picture of his father atop a black horse. In 1913 or 1914, Bob's dad had ridden into Lander from his homestead west of Crowheart, a distance of more than 65 miles, to get the picture taken to send to a girl, Anna Oden, of Sweden. Anna must have liked what she saw, because in 1915, despite the war, Bob's father-to-be made the trip to Sweden and brought her back. They were married upon their arrival in Dubois.

Bob's dad had an eye for good horses, and around 1920, in an effort to upgrade his own, he acquired a leggy sorrel mare from Dick Dennison, owner of the Bear Creek Ranch on a tributary of the East Fork of the Wind River. This whole area was referred to as "Little Scotland" because of the large number of Scottish immigrants who settled there and took up cattle and sheep ranching. Several of these ranchers were known to breed above average horses.

Dennison was a serious breeder who had a fancy for thoroughbred carriage horses. The mare he sold Bob's father had four generations of Hambletonian breeding behind her and got the reputation for outrunning anything put up against her. She had a foal every other year until 1938 when she had her last, a filly probably sired by a stallion owned by Tom Bain, one of the Scottish ranchers on the East Fork, who also bred notable horses. Despite this slight ancestral uncertainty, the filly she dropped was almost a mirror of her mother, sorrel and long legged; and when she matured, like her mother she was reputed to have outrun everything in Wind River country.

After Bob's dad died in 1931, Bob's older brother George pretty much took responsibility for the Westman operation, but the Great Depression and mounting unpaid taxes soon forced Anna Westman to sell the ranch. Without a home, the three Westman boys were forced to survive as best they could. Bob took a job tending cattle for Walt Knollenberg; and his younger brother John, before moving on, sold the Westman horses including the sorrel mare, to Lyle Bessy of Riverton. Her last colt had just been weaned, and because he had a promising appearance from his sire, a quarter horse stallion owned by George Conwell, the Westman boys decided to keep him. Bob named him Rusty.

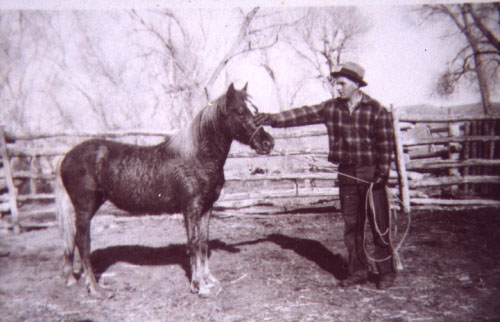

pictured above, tried to gentle Rusty as a colt, but with minimal success.

As a selling point for the horses, John pointed out the sorrel mare to Bessy, praising her for her speed and utility as a cow horse. Once Bessy, something of a horse trader, found John's words rang true, he decided to make a buck by selling the mare to Frank Robbins of Glenrock, who put on rodeos and always had his eyes open for a flashy horse.

In the meantime, Bob and his brother George broke Rusty to ride. They did it in the traditional way; with the hackamore rope snubbed pretty close to the saddle horn of another horse, they took Rusty out for long runs to get him used to Bob being on his back.

Rusty

was only half broken when Bob went to war, Okinawa, 1944, and he hadn't improved

any when Bob returned in 1947, shrapnel and all. Rusty was still full of fight.

After getting bucked off a couple of times, Bob managed to strike a truce

with Rusty, and soon could depend on him as a mount which would no longer

buck him off or run away with him. Rusty quickly learned to ignore the sound

and motion of a whirling loop, and would even pull fence posts and brush behind

him when such was needed.

Rusty's story could be concluded by saying that he lived a respectable life

as a "pretty good hoss" as Bob jovially put it. He stretched out

his share of cows and dragged innumerable calves to the branding fire.

But another story emerges from this tale about Rusty. Indeed, the story of Rusty's mother might conclude with her becoming just another fast rodeo horse in Frank Robbin's string, except that she gallops into the life of a legendary wild stallion who immortalized her.

During the 40's, rounding up wild horses in the Red Desert of Wyoming was still a commercial enterprise. One day, Fred Murray of Nebraska, a friend of mine, spent the better part of an afternoon telling me stories of how his father, Ivan, along with a couple of other wranglers made a living off catching and breaking wild horses in Wyoming, Utah, and Montana. They moved from herd to herd, catching wild horses from one, and breaking them to ride on their way to the next bunch. They stopped at whatever towns were on the way and sold these mounts to buyers interested in owning an authentic wild horse.

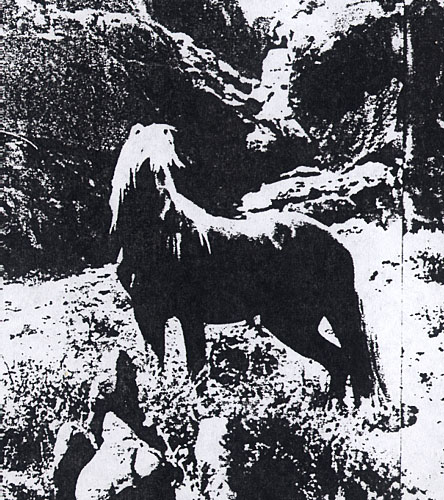

In 1945, the elusive, wild palamino stallion given the name "Desert Dust" was photographed north of Wamsutter, Wyoming by Verne Wood, just before the horse made his last dash for freedom. It was a dramatic scene which spirited his picture into all the local newspapers. For years, Desert Dust was featured on nearly every postcard rack in Wyoming. He stood statuesque on a sparsely sage-covered hillside framed against a massive sandstone ledge. Before his last dash for freedom he was holding his head high, his ears, frozen short at birth, giving him an additional look of toughness and stamina.

July 12, 1945, just before his capture by Frank Robbins

Among the horsemen present that last day of Desert Dust's freedom was Frank Robbins of Glenrock. He was mounted on Rusty's mom, the athletic Westman mare Lyle Bessy had sold him. When Desert Dust made his break for freedom, Robbins put his spurs to her, and she simply ran the stallion down. That mare gave Robbins the most famous of his wild equine trophies. We know no more about Rusty's mother, but we do know some further details of Desert Dust and Rusty.

Desert

Dust was certainly a drawing card for Frank Robbins' rodeos, but there

are dangers to being famous. While grazing in Robbins' pasture, Desert

Dust was gunned down from the highway. Then, not content with the mere

senseless destruction of another's property, the psycho that shot him

entered the enclosure and mutilated the carcass by slashing it with a

knife. There is no record that the criminal was ever apprehended.

A couple of years after the butchery of Desert Dust took place, Bob Westman,

in his prime, was riding Rusty through the gate of the Winchester cattle

ranch.

Bob worked for the Winchesters through 1951. Although he loved ranch work, he intended to marry, and it was hard for him to justify ordering his long range plans around being a full time ranch hand. Many of us remember the $150.00 a month, with room and board. Bob looked to a more urban area where there was adequate housing and better pay.

When he departed the Winchesters Bob took Rusty with him, and for a time he hired on temporarily at various cattle operations close to the town of Hudson where he and his bride, Boneta, had settled. But boarding Rusty became more and more difficult, especially after Bob left ranch work altogether, and he felt he had to sell him.

The owner of a cow-calf operation out of Hudson, Albert Homec, showed an interest in Rusty. Homec thought such a spirited horse, in spite of his singular choice of who would sit on his back, could, with patience, make a good cow horse for his own hands.

But

it was not to be. Even at fourteen years of age, Rusty went right back

to unloading anyone who got on his back. So, Homec, wishing to recover

his lost investment, called a rodeo contractor, Bill Frank, to come look

at the horse, and Frank bought Rusty for his bucking string.

When Bob discovered Rusty's fate, he felt he had betrayed his horse. His

only consolation was that he had kept his saddle and bridle; at least

he still had his tack.

As Bob and I corresponded, images of him and Rusty back on the Wind River began flashing in my mind: the two of them on the yearly cattle drives, framed against the colorful badlands east of Dubois, and again Bob dismounting at the cow wagon parked on Dry Creek where my mother, the cook, was serving the evening meal.

Like Bob, I became vexed with the question of what ultimately happened to Rusty. Bob didn't think Rusty would have made it as a rodeo horse; at fourteen he would have been too old. Bob even entertained the unthinkable, that if Rusty hadn't lived up to the Frank's expectations, he might have been sold as a canner. Nevertheless, Bob knew Rusty hated anybody else on his back. Maybe. . . .

My interest now kindled by the possibilities, I tried calling Bill Frank on the phone only to learn he had died a couple of years earlier. But his son, also Bill, had been equally involved in the family rodeo enterprise, so I called him. Young Bill and I had attended high school together in Lander, and I knew him well. I told him everything I could about Rusty, but the Franks had bought and sold so many horses, many of them sorrels, that except for the best buckers he could not remember one from the other. Anyway, the name Rusty meant nothing. Even if Rusty had been one of their better buckers, he would have been given a rodeo name, something like "Prison Bars," or "Death Valley," and that would been the only possible way Bill might have recognized him. The only thing he could assure me of was that if they bought a horse from Homec it was because he was a bucker. Any rancher could sell horses to the cannery at the sale barn.

Then

Bill asked me what year I was talking about. I said most likely 1960 or

61. That was when Franks were in the thick of the rodeo business, but

also, Bill informed me, when they sold their bucking horses to Buster

Ivory, a rodeo contractor who took them to Europe to put on rodeos there.

So, if Rusty was in their bucking string when they sold, he went with

Ivory.

Man! Rusty in Europe? No one who had ever tried to ride Rusty after Bob

sold him to Homec would deny he had become a bone-jarring bucker. However,

being realistic, at Rusty's age, he would not have had much left for very

long. But he would have given his best! Perhaps he ended his career as

a bucking horse in Denmark or France.

Personally,

I favor France. When it comes to horses, the French have good taste. What

would Rusty's final and finest hour have been in France?

Knowing something about French tastes, it is entirely possible that he

was borne by stylish maitres de table into numerous French

parlors on polished silver platters, placed on elegantly covered tables

set with candles and flowers, and served with a hearty Burgundy.

At least I've saved him from the cannery!

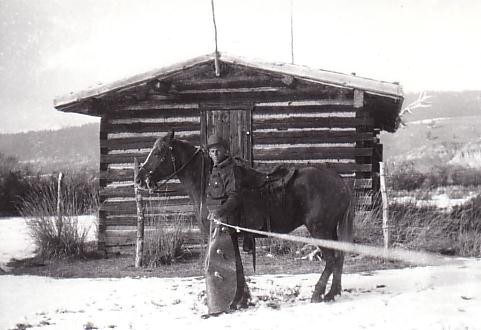

Beyond Bob's and my memories, Rusty will not be forgotten. As a young man Bob took pictures of himself and Rusty in front of Mountain Meadows Cabin, a classic piece of log cabin architecture, built by Walt Knollenberg during the first quarter of the last century. Mountain Meadows is located eighteen miles from the old Westman place, up Meadow Creek which runs down from Crow Mountain.

For thirty years, Knollenberg kept a log of everyone who ever visited the Mountain Meadows Cabin, including many old timers who had homesteaded on the upper stretches of the Wind River. Their names and dates were faithfully recorded on the cabin door.

Then, a few years ago, an act of vandalism to the cabin–a collector removed the door for a souvenir–brought it considerable public and private interest. This interest was due not only to the historical significance of the log written on the door, but to the fact that Gerry Spence, the famous Wyoming lawyer who had earlier owned the property, took the vandalism personally. He advertised in most every newspaper in Wyoming for information on the missing door, offering a reward for its return. The door was eventually returned under secretive circumstances, and it, now in Spence's possession, will obviously never be put back on the cabin.

With all the attention focused on the history and culture of the Wind River and Crow Mountain area, Bob not only got his best picture of the cabin, Rusty and himself, published in the newspaper, but he also took the picture to Cheyenne, the state capitol, where the curator hung it in the State Museum.

So, Bob and Rusty now hang in the Barrett Building. Bob in his chaps and other items of cowboy attire merges his authenticity with both his profession and the Wind River cattle country itself. Rusty saddled with Bob's gear is alert, ready to go as Bob trips the shutter with a long piece of string which leads him and Rusty into their niche of history.